The Academic Research Flywheel

This post originally appeared on LinkedIn.

Most of us suffer from a problem of infinite ambition and finite resources. A common mistake we make is to take the resource gunpowder we have, and make hundreds of small bullets and shoot. Some bullets miss, and some others hit. Instead, what if we only shot a fraction of our bullets, identified the holes we made, and shot a giant cannonball with the remaining gunpowder to obliterate the target?

All three phases are important. If you do not shoot enough bullets, you will not make enough holes. If you do not spend the time identifying the holes, you will not orient your cannonball correctly. And, if you do not take the often laborious effort of building the cannonball, you will not obliterate your target.

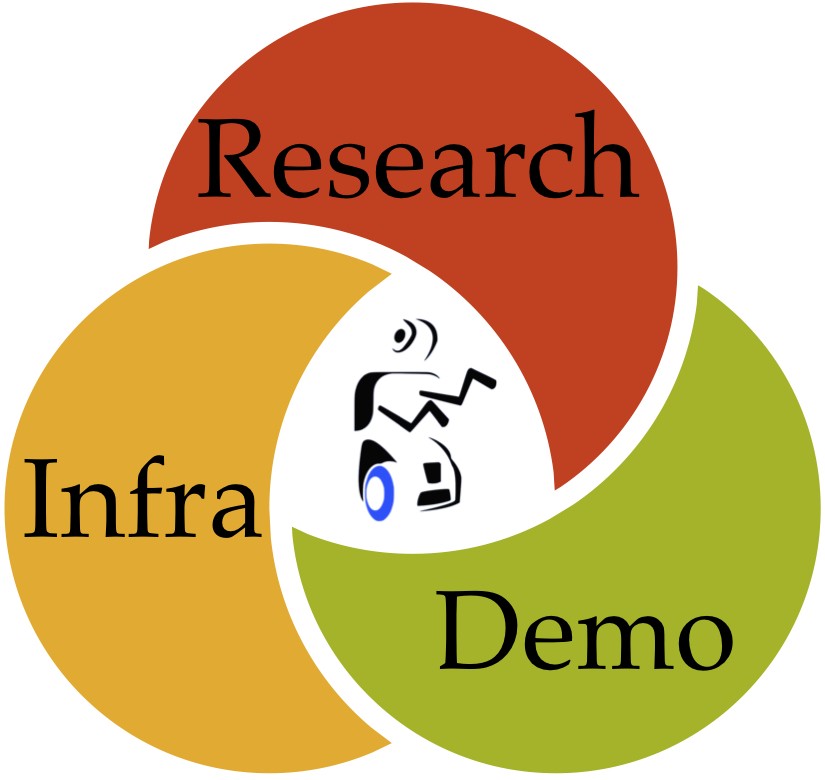

At my lab, we have specific names for these three phases.

The demo is something we put together quickly and scrappily. It’s our small bullet. We often try to make it fun. For example, we put together a bartender demo with our robot HERB to pickup and handover soda cans to people. Some things worked and many things did not.

A common mistake is to assume that the failures are relevant and jump to building a giant cannonball to address them. Often, demo failures are due to mistakes and errors rather than genuine problems. How does one identify the real problem?

The infrastructure is a hardening of the demo that systematically works through all of the mistakes and fixes them to the best of our abilities. We are careful not to introduce any new ideas in this step, and focus exclusively on fixing mistakes. At the end of this phase, we have usually reduced our failures to genuine problems with our ideas. For example, even after our best efforts at calibrating our system and tuning our perception algorithm, HERB was clumsily failing to pick up 1 out of 20 soda cans. Now we have identified the real hole.

The research is the new idea we are forced to invent because of a clearly identified pain point with our current set of ideas. When I do research it is not because I have a cool idea, but it is because I am in agony over the failure of my existing ideas. For example, we realized that our existing paradigm of moving to a pre-grasp pose and closing our fingers was very sensitive to even small errors in the relative pose between the hand and the soda can. A mere 5mm would result in the soda can slipping away from the grasp. So, we invented the push-grasp, an open-loop policy of pushing forward while grasping that guaranteed, via quasi-static physics, that the soda can would always curl into the hand as the fingers closed. More importantly, push-grasping changed the way the community looked at grasping, from a static problem to a dynamic and complex interaction between the hand and the object that, surprisingly, could be modeled via simple physics.

So, where is the flywheel? The nice and frustrating thing about robotics is that every target you obliterate merely reveals the next target. Grasping works now, well how about feeding people marshmallows? On we go to the next demo, building up our quiver of arrows.

Skipping phases leads to come common research failures. Here’s a few of them:

- The YouTube Star: who loves shooting small bullets and declaring success, never really obliterating the target, but decreasing everyone else’s funding gunpowder claiming the problem is solved.

- The Magician: who loves building their favorite cannonballs and shooting them at make-believe targets that only their cannonballs can reach. Sometimes they are even charismatic enough to blindly convince others of the existence of these targets.

- The Etsy: who is so in love with the artisanal process of building the perfect hand-crafted cannonball that they don’t really care if it only obliterates a tiny target, but beautifully. I am grudgingly in love with the Etsy, but can never bring myself to wasting so much time. So, go build your own academic research flywheel! I am, as always, happy to help however I can.